18

|

design

mag

studio.”What is more, according to Wang:

“A hundred years ago in China, the people

who built houses were artisans; there was no

theoretical foundation for architecture.

Today, an official architectural system has

been established, but I chose handicrafts

and the amateur spirit over the system. For

myself, being an artisan or a craftsman is an

amateur or almost the same thing.”

The Amateur Architecture Studio has won

several major awards for its work, including

the Architecture Art Award of China in 2004,

the Holcim Award for Sustainable

Construction in the Asia Pacific in 2005, the

Global Award for Sustainable Architecture in

2007 and the Schelling Architecture Prize

in 2010.

“To look at the state of the [architecture]

profession, it would seem that anything is

possible, and more often than not, we get

anything!” remarked the Australian architect

Glenn Murcutt, a former winner of the Pritzker

Architecture Prize himself and one of the

judges who awarded it to Wang this year.

“Form for its own sake has become a

superficial discipline.Wang Shu and Lu

Wenyu, however, have avoided the

sensational and the novel. In spite of what is

still a short period in practice, they have

delivered a modern, rational, poetic and

mature body of varying scaled public work.

Their work is already a modern cultural asset

to the rich history or Chinese architecture

and culture.”

The Amateur Architecture Studio is best

known for the following buildings in China:

the Library of Wenzheng College (2000) in

Suzhou; the Ningbo Contemporary Art

Museum (2005) in Ningbo; Five Scattered

Houses (2005) in Ningbo; the Xiangshan

Campus of the China Academy of Art

(2004-2007) in Hangzhou; Ceramic House

(2006) in Jinhua;Vertical Courtyard

Apartments (2007) in Hangzhou; the Ningbo

History Museum (2008) in Ningbo; and the

Exhibition Hall of the Imperial Street of

Southern Song Dynasty (2009) in Hangzhou.

Wang Shu frequently uses recycled building

materials, especially old clay bricks and roof

tiles, which unfortunately have become far

too plentiful in China in recent years due to

the indiscriminate demolition of the

country’s old low-rise buildings in order to

make way for new, often foreign-designed,

multi-storey developments. For example,

Wang salvaged over two million roof tiles

from traditional houses that had been

demolished as a result of this profligate

pursuit of progress, and reused them on his

award-winning design for the Xiangshan

Campus of the Chinese Academy of Art.

For the tenth International Architecture

Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2006,

Wang created “Tiled Garden,” an

installation that consisted of 66,000

semicircular grey roof tiles that had been

recovered from demolition sites in China.

This was his subtle yet powerful protest

about the current rapid and often

thoughtless destruction of China’s

traditional everyday built environment.And

the amazing textural walls of perhaps his

best-known building, the Ningbo History

Museum, were constructed from about one

million recycled bricks and tiles salvaged

from old buildings that had been razed in

the region of Ningbo.

Recycled building materials often seem to

have magically absorbed the essence of a

place, which is one of their characteristics

that Wang Shu has taken advantage of to

stunning effect on several occasions.

“Everywhere you can see, [people] don’t

care about the materials,” remarked Wang

Shu while discussing his Ningbo History

Museum.“They just want new buildings,

they just want new things. I think the

material is not just about materials. Inside it

has the people’s experience, memory –

many things inside. So I think it’s for an

architect to do something about it.”

this opening.

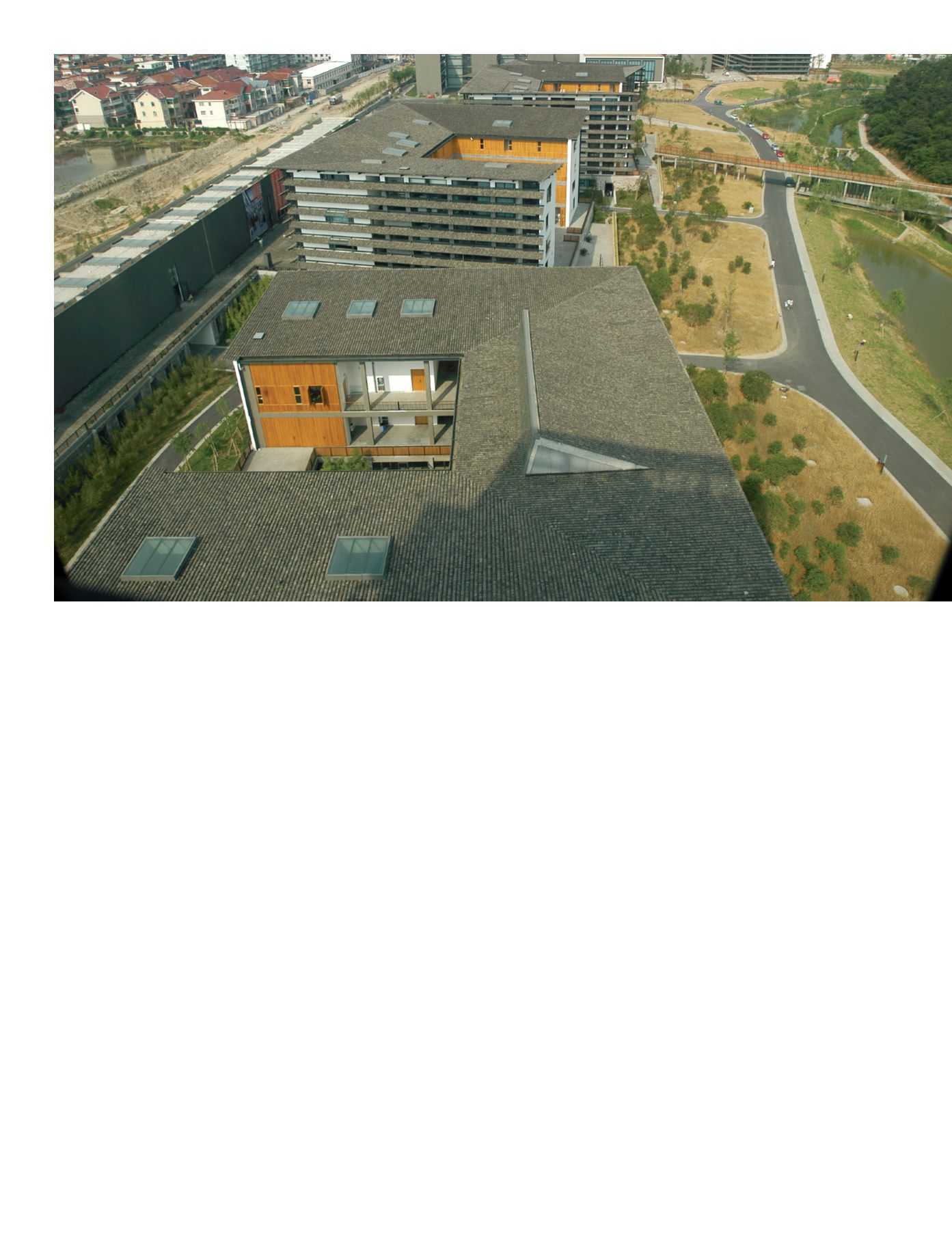

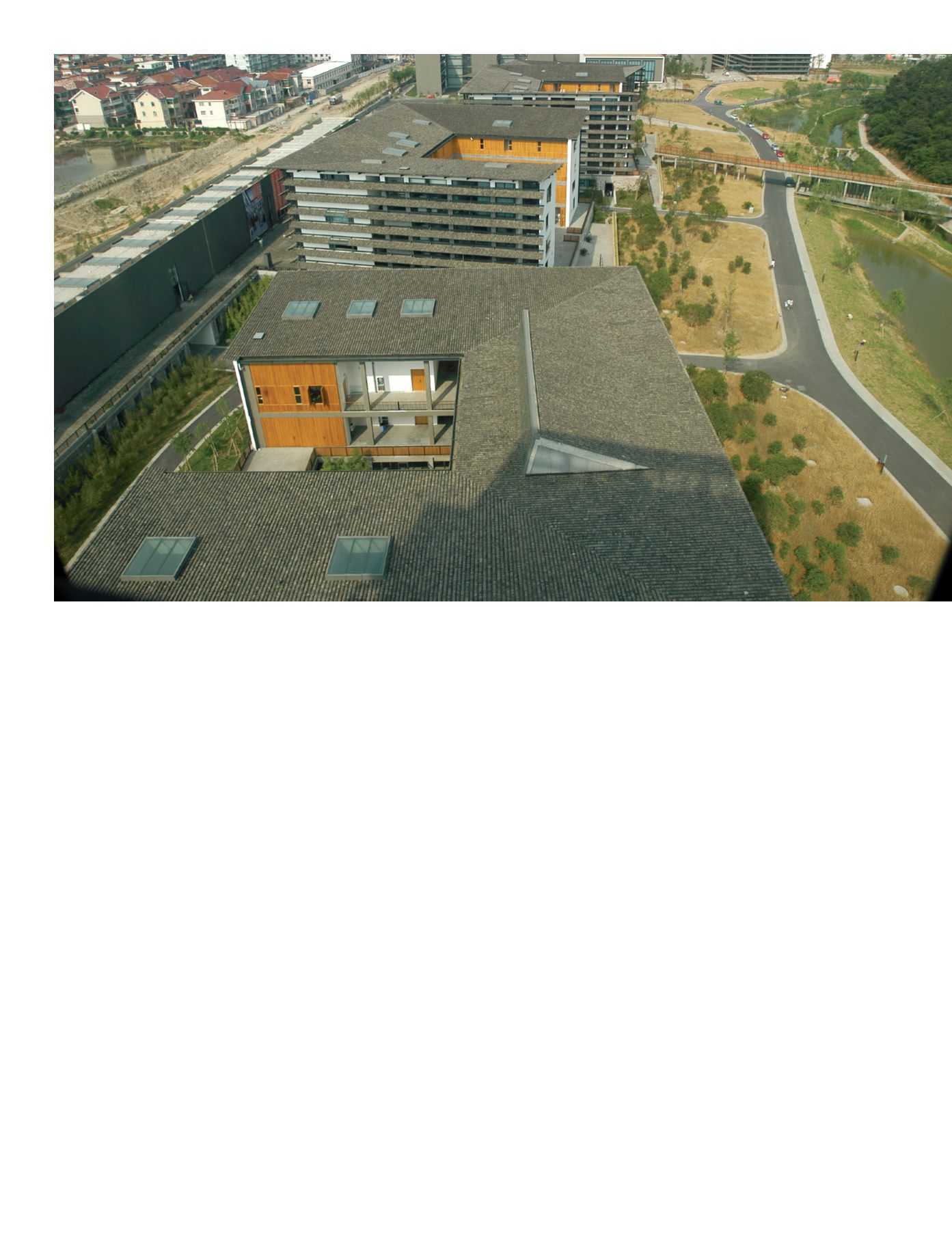

Stage one of

the Xiangshan Campus of the

Chinese Academy of Art

(2004) in Hangzhou, designed

by the Amateur Architecture

Studio. (facing page) Ningbo

History Museum.