70

|

design

mag

Since its establishment in 1997,

m3architecture has developed and

maintained a reputation for a considered

and innovative design approach that is

anything but formulaic.

“We have an interest in making every project

specific to the client and to the site and its

users,” explains m3 director Mike Lavery.“We

are particularly interested in public

engagement in projects, how people other

than the primary user experience a building.”

Another m3 hallmark is adding an element

of surprise or joy (often under-the-radar) into

a project.

There is no m3 house style, no focus on a

particular material palette, nothing that says,

at least overtly, that this is an m3-designed

building.“There’s a way of thinking perhaps,

that’s an m3 way, but not a style,” Lavery

contends.This way of thinking is no doubt

informed by a collaborative process that

sees every project influenced by the

involvement of all directors.

Mike Banney, Mike Christensen and Mike

Lavery were at university together and

worked in various combinations before

forming their partnership. Ben Vielle, m3’s first

employee, was invited to become a director

soon after.

The practice now employs 16 including the

directors, working from a refurbished carpet

warehouse on the edge of Brisbane’s CBD.

Their work is mainly in institutional projects for

state and local government, schools and

universities, although m3 does some

commercial and residential architecture.

Institutional buildings must be robust,

adaptable and low maintenance, and not

surprisingly brickwork fits these requirements.

“Although a brick has high initial embodied

energy, this is dissipated over a 40- or 50-year

period making it a wonderful selection and I

think hard to beat,” Lavery contends.

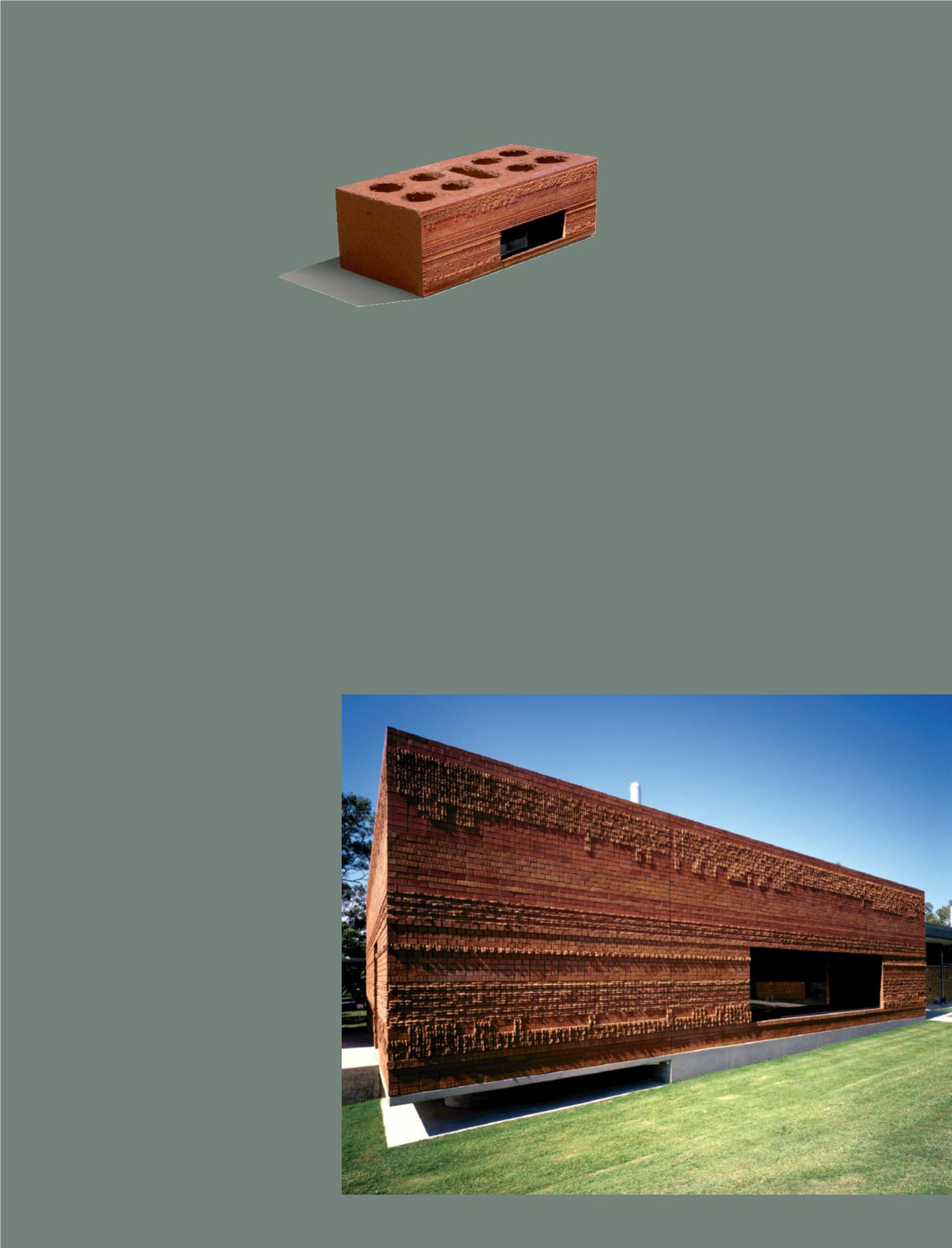

m3architecture came to prominence in 2002

with the Health and Microbiology Laboratory at

The University of Queensland’s Gatton campus,

aka the Brick Box.

Gatton is a typical campus of the 1960s and

‘70s with a series of brick buildings that Lavery

describes as “very respectable and pragmatic,

but lacking excitement.”The external patterning

of the Brick Box challenged all that while

retaining (and respecting) the materiality of the

existing campus.

The highly-patterned building skin began life as

a series of self portraits developed by artist

Ashley Paine.“The portraits are a collection of

works that sought new representations of the

artist,” said the project’s design architect

Michael Banney in an interview at the time.

“These were developed through a variety of

media and processes and ultimately transcribed

into another medium/process, namely

brickwork.”

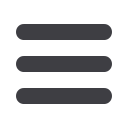

Two brick types were chosen, one smooth face,

the other textured, both with different core hole

patterns. Some whole bricks were laid as

alternating courses of headers and stretchers,

and others in a stack bond.The balance of

bricks were bolster cut at different points to

produce differing degrees of texture.To minimise

wastage, all brick halves were utilised.

“This laboratory was a fantastic opportunity to

show what the prosaic brick could be, a

masonry unit turned into a piece of pottery,” says

Mike Lavery.

The craggy texture of the exterior is in stark

contrast with the clinical white and stainless

steel interior.A low-slung picture window allows

views for passersby, chipping away at the

mystery inside.

Not surprisingly the Gatton project won a string

of architectural awards and was featured in

many publications including the 2004 edition of

the Phaidon Atlas of Contemporary World

Architecture.

The laboratory encapsulated m3’s approach

then as it does today, with its consideration of

specificity and materiality, to the site, the project,

its users and to the wider campus population.